- Home

- V. M. Whitworth

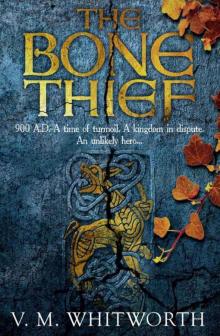

The Bone Thief Page 23

The Bone Thief Read online

Page 23

He swallowed painfully. Loving the Lady was so familiar, so safe, so hopeless. Here and now, by contrast, every beat of his thudding heart said danger. But he couldn’t tear his eyes away. He had no idea how long he had been standing there. She was so very beautiful.

He realised with a sudden uprush of shame that he was spying on her. He pulled back. But she stood now, turning, bending forward. Her already diaphanous linen was splashed with water to distracting effect. Had she seen him, heard him breathing? She reached for the protection of her long green tunic, still singing softly in her throat. He pressed himself back into the scrubby goat-willows. The trees were barely coming into leaf, and she’d see him if she bothered to look through the reeds. But she was covered now, and, relieved and emboldened, he moved out into full view.

‘Wuffa!’ She didn’t sound startled. Glad, if anything.

He stepped forward.

‘What on earth are you doing?’ he asked. ‘You’re all wet. You’ll catch cold.’

‘Come here,’ she said. ‘Let me wash your face.’

Still hardly knowing what he was doing, he went down to join her, and she dipped the cuff of her tunic in the water and scrubbed hard at his face. He could feel her breath on his cheek. When the dried blood got wet it smelled fresh again, and a wave of nausea heaved over him, making for an uneasy mixture of queasiness and desire. He asked again

‘What have you been doing?’ he asked again.

‘Sorting your bones.’

‘What?’

She looked very pleased with herself, almost girlish, and, for once, unguarded. She knelt again now, rinsing the blood out of her sleeve, but she turned her face up to him.

‘Look. We must have found the right grave. There are two different people here.’ She moved to one side and gestured at two piles of bones.

Frowning and fascinated, Wulfgar came closer to kneel at her side and have a better look.

‘See? This person, já?’ It was the pile topped by the skull. ‘He didn’t die so very long ago. Thirty years, did you say? That could be right. The joints even have some sinews still attached. And the bones are quite light in colour.’ She offered him a femur.

He nodded, tight-lipped, but didn’t touch it.

‘Now these –’ she moved on to the second pile and found the matching bone ‘– these are old. See? And the bones are dark brown, very smooth.’

‘Polished,’ Wulfgar said, his voice cracking as he reached for it. ‘Venerated. Where did you learn so much about bones?’ He thought of devoted hands for over two hundred years, caressing these bones, bearing them in procession, wrapping them in eastern silks; of the lips of pilgrims, abbots and kings, pressed to them, murmuring in prayer, whispering to them all their hopes and dreams and fears. If he hadn’t already been kneeling he would have knelt then.

St Oswald, he thought, you are here, you are really here, in my hands. He felt the tears rising as he pressed his lips to the silky brown bone. Oh, my dear, dear Lord and Saint. Pray for the Lady, pray for all Mercia, oh, pray for us.

It hadn’t taken a miracle to know the saint when they met him, only common sense. Gunnvor’s common sense. The practical abilities of a woman, a heathen and a Dane. But perhaps that was the miracle.

Trying to mask his emotion, he asked, ‘What about the fragments of the reliquary?’

‘Those bits of old wood? Here. I didn’t want them to get wet. They’re so fragile already.’

Wulfgar nodded.

‘We’d better get back. The others will be wondering where we are.’ He started pulling bones from both piles with the aim of getting them into Gunnvor’s sack. His hands were still shaking.

‘You’re taking the other one too?’ she asked in surprise.

Wulfgar nodded again. ‘He’s guarded the saint for us for thirty years. The least we can do is thank him. I’ll see he’s reburied with all ceremony when we get him home.’

‘I have more sacks,’ she said. ‘Keep them separate?’

They started sorting and packing. Gleaming ribs, the strange, flanged discs of vertebrae – so many ribs! so many vertebrae! – a pair of shapes like angel’s wings that Wulfgar puzzled over until he realised they were the saint’s hip-bones. The little lumpy bones that had made up his feet. It was a profoundly intimate process.

As they worked side by side in silence, Wulfgar felt an extraordinary sense of contentment stealing through him. He could have wished the moment to go on for ever.

But, all too soon, St Oswald had been reduced to a neat package, as long as a femur and wide as a hip-bone. He should be wrapped in finest white linen, Wulfgar thought, in silk as fine as moonbeams, in the softest lambswool worsted … That length of ragged sacking would have to do for the meantime.

The other, the Bardney monk, made for a bulkier, ungainly pile, his lower jaw still attached to the skull, his pelvis articulated. Wulfgar wrapped the fragments of frail wood in yet another piece of sacking; he longed to puzzle over their arcana but it would have to wait.

Gunnvor was kilting up her green skirt, but she paused just as they were bending to pick up their burdens and return up the bank.

‘Wuffa?’

‘Mmm?’

‘Aren’t you going to say thank you?’

‘To the monk of Bardney?’ He looked at the bulkier of the two sacks. ‘We’re taking him with us, aren’t we? He must know how grateful we are. We’ll bury him in the minster-yard—’

‘Not to your bony friend there.’ Her voice had grown acerbic. ‘Thank you to me, I mean.’

He straightened at that, and flushed.

‘You shouldn’t have taken the relics off to wash them without asking me. You shouldn’t—’

‘What?’ She looked up at him. Her eyes were bright, but that old mocking tone had come back into her voice.

His flush deepened.

‘Never mind.’ It was the memory of her body, the thin wet linen barely shielding her, so soft and white and vulnerable, and so close to the saint’s bones. Too close. And singing, as well. It hadn’t seemed right.

She looked down at the parcels. ‘All this bother for a bit of charnel. Who was this Oswald, anyway, that you price him so highly?’

‘Saint. Martyr. King.’

She shrugged. ‘Words.’

He was silent for a moment. His heart was full of things he wanted to make clear to her. And what’s my faith worth, he thought, if I can’t even explain to this woman why St Oswald could be the saving of Mercia?

‘I—’ he gestured in frustration. ‘Oh, it would be so much easier if I had my harp.’

She raised her eyebrows, and he thought for a wonderful moment that she was about to smile. Instead, glancing at the wet bank behind her, she settled down on her haunches.

‘Go on. I’ll imagine the harp.’

‘Right. Yes.’ Feeling wrong-footed, he cleared his throat. ‘Well. This is the one my uncle taught me. Listen! Oswald the noble, Northumbria’s king, was wise and worthy in wielding his kingdom …’ He started off down the well-trodden path, chanting the words at first, but as the story drew him in he began to sing them properly, his left hand beating time against his thigh:

‘Hard to the heathen

hostile against him;

Mild to his own folk,

merciful and fair;

To orphans and widows

always a guardian.

He first founded,

fair in God’s eyes,

Lindisfarne

loveliest of monasteries,

Brought from Iona

the first Bishop,

Aidan, Christ’s darling …’

The tale unfolded like a rich tapestry: battles the warp; miracles the weft. He felt as though he were an actor in the tale, kneeling with Oswald’s still-heathen soldiery before the wooden cross the saint had raised at Heavenfield … Victory after victory, and then the turning of the tide, the last great battle against Penda of Mercia …

Hateful heathen

&n

bsp; hard oppressed him,

Penda the pagan,

the promise-breaker.

He perished at last

at Penda’s hand.

‘God send salvation

to their souls,’

Oswald the faultless

cried as he fell.

Merciless Mercians

martyred the king,

Hacked off his head

and his noble hands,

Set them on high

as a horrible sign …

He bit down hard on his lower lip and blinked furiously.

His body they buried

on the battlefield,

A nameless pit

the noble one received …

It was no good. His voice was wobbling too much to carry on.

‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘Sorry.’

‘But what happened next?’ Her eyes were shining, and her lips were slightly parted.

He knuckled his eyes.

‘His hearth-men rescued his head and his arms from Penda’s scaffold and took them back. North of Humber. They’re still there.’

She frowned.

‘And it was the Mercians who killed him?’

‘Penda, who killed him, was Mercia’s last heathen king. It wasn’t many years later that St Oswald’s niece married a Christian king of Mercia. Penda’s son, as it happened. She had her uncle’s body exhumed from the battlefield and taken to Bardney. It’s all in the song.’ He looked down and saw the bags at his feet as though for the first time. ‘And now he’s here. In our care.’ He felt the blood drain from his face, heard the ringing of distant bells in his ears. He stumbled.

‘Careful, there.’ Gunnvor was his side, supporting his elbow. ‘You need to sit down …’

He nodded, still dizzy. ‘Thank you,’ he said at last, and in saying the words he found that he meant them with all his heart. ‘Oh, Gunnvor. Thank you so much, for everything.’

Her eyes found his then, and for once there was no mockery in them.

‘Wulfgar of Winchester, you are welcome,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘I’ve never met anyone like you.’

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

THEY STOOD THERE in the pearly light, looking at each other. Wulfgar started to say something, but she held up her hand. He was almost glad; he was so far out of his depth.

But she wasn’t looking at him any longer. Her head had jerked round, to look eastward, over the marsh.

Then he heard it, too. Too steady to be the splashing of water-birds. A rhythmic creak underlying it. They strained to hear, a brief moment that felt as though it was lasting for ever. Splash, and creak, and splash, and creak …

‘It might just be night fishermen, going home,’ he whispered.

‘It might.’ She was still listening. ‘And then again—’ She turned on her heel, and pelted back up towards the lambing hut.

Wulfgar, taken aback, waited a moment or two longer, long enough to see emerge from the mist two big, flat-bottomed punts of the sort that fowlers used, each poled by a man standing at the back, riding low in the water because they were laden with more men. Many more. The mist came down again, the spell was broken. He hurtled after her, all three sacks of bones and wood clutched in his arms.

By the time Wulfgar reached the thorn-hedge, he was yelling fit to crack his throat: ‘Get out! Get out of the yard.’

Leoba had been swaddling her sleepy children; now she was stuffing them into a shallow, wide-mouthed pannier as if she were readying ducklings for market. Ronan grabbed the pannier from her and lashed it to the back of the mule before swinging round and drawing his sword. He slapped Ednoth on the shoulder and at once the two of them, blades out, were heading for the gap in the hedge, shouldering past Wulfgar. Gunnvor, who had headed straight for her grey mare, was vaulting onto her back and pulling the reins up short, wheeling the horse.

‘Get on the mule,’ Wulfgar shouted at Leoba.

She stared at him for a moment before hauling herself onto the mule’s wooden saddle.

‘Go! Go!’

There was shouting from the marsh. He looked round. The punts were grounding in the mud, men jumping out. They were running. More shouting.

‘Come on, lad!’ Ronan shouted. He and Ednoth were blocking the way up the slope, or trying to.

Wulfgar could see only one end to this story. He tried to think, his heart pounding so hard it shook all his ribs. What was really important here? No time to think things through.

‘Go!’ he shouted again at Leoba. ‘Go, with the children!’ And then, ‘No, wait!’ He grabbed the slim, bundled sack of the saint’s smooth, ancient bones and thrust them up into Leoba’s arms.

And Gunnvor was there on the other side, grabbing for the mule’s bridle, ramming her heels into the grey mare’s flanks.

‘Já, we’ll see you in the Wave-Serpent.’

Leoba had gone white, but she nodded, tucking the swaddled bulk of the relics into that useful fold of her dress as though it was another baby. Then she picked up her own reins and drummed the startled mule with her own heels, and the two women were away up the track.

Had their attackers seen them?

Wulfgar was still staring after them when his arms were grabbed from behind. Other men were disarming Ednoth and Ronan, with humiliating efficiency. Ten armed men in the enemy party, Wulfgar found himself tallying, against a priest, a subdeacon, an untried boy. And Thorvald’s body, lying unnoticed under the pile of brushwood some thoughtful person – Ronan, he thought, it will have been Ronan – had stacked to keep the foxes at bay.

Once they had been rounded up and put under guard, the other men started piling up their goods, stacking the saddlebags in the punts.

It was only then that Wulfgar realised: their orders have been changed since last night. This time, they must have been told not to hurt us. Or, not more than they can help.

Why not? he wondered, at a loss. Last night they meant to kill. And now they’ve got a grudge. We killed, how many, last night? Four?

His eyes flickered again to where Thorvald’s body lay in the lee of the hedge. Why don’t they just kill the rest of us? If it’s the relics they’re after, he thought, they must know we’ve got them.

But no. Once their attackers were confident they had everything that might be part of their baggage, the prisoners were rounded up and prodded towards the boats. Their hands weren’t even tied. And no one fought back, once they’d been disarmed. Even Ednoth could see they had been outnumbered.

Wulfgar had assumed their captors were southerners but their voices had Thorvald’s accent, so broad Wulfgar could hardly follow their speech, such as it was. They didn’t talk much. They had their orders, and they were sticking to them.

When everyone was aboard and their stuff was shipped, the punts rode even lower in the water. Wulfgar thought then, of course, they have to be Bardney men. How would West Saxon strangers find their way through this wilderness of reeds? The marsh was no cheerier a place in the growing day than it had been by moonlight.

For the first time he found himself wondering how old Ronan was. The priest’s skin looked even greyer than the dawn light warranted and there were dark blotches beneath his eyes. As the boats creaked and splashed their way through the reeds, Wulfgar felt a growing sense of detachment. It was as though it were all happening to somebody else, someone he’d heard about in an old song.

They were all going to die, and soon.

But his own job was done.

Leoba was safe, and the children. And Gunnvor.

And St Oswald.

As safe as I could have made them, he thought sadly. But I would so have liked to know what happens next … His heartbeat reminded him of the pounding of the horse’s hooves, thudding away up the track – they’re safe, they’re safe, they’re safe. They must be, he told himself. They must have got away. Over and over, the same tune, keeping time with the soft liquid sound of the boat as it was poled through the shallow water.

The boats

travelled far more quickly than Thorvald and Wulfgar and the others had the night before, squelching on foot through the dark. The earth banks and thatched roofs of Bardney were before them again all too soon, silhouetted against the rising sun. As soon as the prows of the punts sank into the mud of the bank, they were hustled out and up the path that led to the main door of the old church. The interior was dark, reeky. They were stopped just inside the door, their captors crowding in hard on their heels. The smoke was eye-watering.

A cackle broke the silence. A woman’s laughter. Then, ‘You mean to tell me, this is your band of warriors?’ The laughter broke out again, ending in a fit of coughing.

‘It can’t be.’ A man’s voice, his accent West Saxon, sullen in disbelief. ‘We were outnumbered. Armed men. Not – not these.’

Wulfgar could see more clearly now, in the dim glow of the banked central hearth, the only source of light other than the doorway and the high small windows. There was no sign of Garmund. A woman of forty or so, a shawl around her head and shoulders, was standing a few feet in front of them, with a man at her side. He was muddy, blood-stained, unshaven.

‘The one that got away,’ Father Ronan breathed in Wulfgar’s ear. ‘Damn him.’

The woman looked each of them up and down in turn. Her face was set in hard planes, though the beauty that had been there once was still visible in the well-modelled cheekbones and the long line of her neck. She turned to shout at someone at the back of the hall. ‘Where’s that southron? I want him.’

‘Still out on the hunt, lady.’ Another servant came forward, wiping her hands on her apron. ‘He and his party went north, up the roadway.’

‘Send after him. Keep these under guard until he gets here.’ She pushed past them.

‘Keep them in here, shall we?’ Their guards sounded at a loss.

The Bone Thief

The Bone Thief